With great interest and appreciation I write this article.[1] It’s not often that I read about an Anglican who’s heard of the Belgic Confession (Confessio Belgica). Rev. John P. Boonzaaijer has actually read it. Even more, he’s thoughtfully compared the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession.

Having an Anglican who’s read the confession of the Dutch Reformed wasn’t always so striking. On both sides of the Channel, the Reformed viewed the confessions and liturgies as expressions of one faith. They were—we are—Reformed Catholics. For example, Theodore Beza compiled the Protestant confessions in 1581 as Harmonia Confessionum Fidei Orthodoxarum et Reformatarum Ecclesiarum. In 1586 this was translated as An Harmony of the Confessions of the Faith of the Christian and Reformed Churches. A new edition was published in 1842. Beza didn’t merely compare the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession; he harmonized them.

Reading the letters of the Reformers evidences this international attitude.[2] Of note is the exchange between Heinrich Bullinger, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, and Philip Melanchthon during the Council of Trent. They expressed a desire for an ecumenical Council of Protestants. Cranmer wrote to Calvin:

Reading the letters of the Reformers evidences this international attitude.[2] Of note is the exchange between Heinrich Bullinger, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, and Philip Melanchthon during the Council of Trent. They expressed a desire for an ecumenical Council of Protestants. Cranmer wrote to Calvin:

As nothing tends more injuriously to the separation of the churches than heresies and disputes respecting the doctrines of religion, so nothing tends more effectually to unite the churches of God, and more powerfully to defend the fold of Christ, than the pure teaching of the gospel, and harmony of doctrine…I have often wished, and still continue to do so, that learned and godly men, who are eminent for erudition and judgment, might meet together in some place of safety, where by taking counsel together, and comparing their respective opinions, they might handle all the heads of ecclesiastical doctrine, and hand down to posterity…some work not only upon the subjects themselves, but upon the forms of expressing them. Our adversaries are now holding their councils at Trent…shall we neglect to call together a godly synod, for the refutation of error, and for restoring and propagating the truth?[3]

In this spirit I review the recent article of Rev. Boonzaaijer. My review consists of commendation and constructive criticism. My purpose is to provide a means of furthering understanding and appreciation. Those within the traditions of “The 39” and “The 3 Forms” mutually must learn from each other.

Commendation

Background

First, I appreciated his opening with background and biography of Guido de Brès and the Belgic Confession (56–57).[4] It’s necessary to read the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession in their own theological, sociological, and ecclesiological milieu. Richard Muller and Willem Van Asselt’s work shows the importance of doing history and theology in its own context. Apart from this we miss authorial intent as well as of the churches that adopted them as confessions (the animus imponentis).

Importance of the Text

Second, Rev. Boonzaaijer pays careful attention to the text and structure of the Confession.[5] There’s a reason for the letters, words, and sentences in any document, especially ecclesiastically adopted confessions. He shows an irenic spirit, not merely pick out an objectionable phrase here or there to preach to his choir. Additionally, he recognizes the overall structure of the Confession (57), including the internal structure of the first section on God (57–59). He also brings out the pastoral nature of the Confession: “we confess” under severe persecution as Kerken onder het Kruis (60).

Irenic

Third, Rev. Boonzaaijer exhibits an irenic and ecumenical spirit. He seeks to build a bridge between the churches of the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession. His words cut to our hearst: “Each communion stands to grow from the other: the English Church from the personal vibrancy of the Belgic Confession, and the Reformed Churches from the solidity of government and liturgy as part of the wholeness of the English Church” (63).

Critique

Arguments from the Order of Articles

First, Rev. Boonzaajier imputes meaning to the Belgic Confession based on the placement of doctrines within it. In a word, he makes too much of the order of the various articles. For example, he makes his points by directing attention to the Belgic’s articles on God and the sacraments.

Articles on God

With regard to the articles on God, Rev. Boonzaaijer rightly points out the Confession’s opening article on God’s nature and existence. Then it moves to how we know this God in creation but especially in Scripture (arts. 2–7). Finally, it confesses the Holy Trinity (arts. 8–9), albeit “very articulately” (57), the deity of the Son (art. 10), and Spirit (art. 11). He makes theological points in noting the order of these articles. First, he claims this “set an early precedent for reformed continental theology that would later be renewed and developed by Karl Barth in his Church Dogmatics.” This precedent led Barth to develop the “Doctrine of the Word of God” before “The Doctrine of God” (58).

In response, this claim is invalid. The same structure is followed by Reformed confessions prior to the Confessio Belgica: Tetrapolitan (1530), Bohemian (1535), First Helvetic (1536), Geneva (1536/37), Waldensian (1541), second Waldensian (1543), Calvin’s Catechism (1545), Large Emden Catechism (1551), Glastonbury (1551), Rhaetian (1552), and Second Helvetic (1561/66).[6] All these open with God then deal with Scripture before moving to the Trinity. There’s a diversity in Reformed confessions such as the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession on how they’re ordered. Yet this wasn’t intended as Rev. Boonzaaijer claims.

His second claim is this order “demonstrates…that…the Belgic Confession resembles more closely the format and order of a Systematic Theology.” In contrast, “the Thirty-Nine Articles are clearly following the structure of the ancient Creeds and Councils of the Church in an organic, covenantal pattern” (58).

In response, one can’t claim the Belgic doesn’t follow “an organic, covenantal pattern.” Its articles follow the flow of covenantal history: God, creation, sin, redemption, the church, culminating in the coming of our Lord. Furthermore, the claim that the 39 Articles follow the creeds while the Belgic doesn’t isn’t demonstrable. The Belgic follows the structure of the Nicene Creed. Both the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession confess the Faith (“I believe”) expressing the work of each Person of the Holy Trinity. Here’s how the he Belgic follows the Nicene Creed:

- God and his Triune nature (arts. 1–11)

- “The Father Almighty” (arts. 12–13)

- “One Lord Jesus Christ” (arts. 14–26)

- “The Holy Spirit” (arts. 22–24)

- “One, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” (arts. 27–32, 36)

- “One baptism” (arts. 33–35)

- “the life of the world to come” (art. 37)

The 39 Articles and Belgic Confession are catholic confessions. de Brès expressed this catholicity in his “Dedicatory Epistle” to King Philip II of Spain:

From this Confession we trust that you will see that we are wrongly called schismatics, promoters of disunity, rebels and heretics, for we not only uphold and profess the chief heads of the Christian faith, comprehended in the Symbolum or Creeds, but also the whole teaching, revealed by Jesus Christ, for our life, justification and salvation, proclaimed by the evangelists and apostles, sealed with the blood of so many martyrs and preserved pure and complete by the primitive Church until at length it was perverted through the ignorance, greed and ambition of her ministers with human inventions and additions, contrary to the purity of the gospel.[7]

Articles on the Sacraments

Rev. Boonzaaijer moves on to “the placement of Baptism in the order of articles.” This “trenchantly portrays the divergent roles these two sets of Articles will play in the Church in the centuries after the Reformation” (60). Boonzaaijer says placing the articles on the sacraments at the end caused the Reformed churches to reduce baptism “to a basic dedication of infants” (60):

The Belgic Confession maintains the catholic tradition in much of its wording, but its tone is already altered to encourage the various strands that will grow out of it in history, from the anabaptism it condemns to the mere dedication many covenantal communities have been reduced to (60).

The good Rev. doesn’t offer any footnotes in his article. Therefore, I’m not sure to which Reformed churches he refers. There are many Dutch Reformed groups in North America. I don’t know anyone among Christian Reformed, United Reformed, Canadian Reformed, Protestant Reformed, Free Reformed, or Heritage Reformed that view baptism as dedication. In fact, these all still utilize the liturgical forms and prayers adopted before and at Dort. Our historic Form for Infant Baptism can’t be understood as mere dedication:

Holy baptism signifies and seals to us the washing away of our sins through Jesus Christ. For this reason, we are baptized into the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

When we are baptized into the name of the Father, God the Father testifies and seals to us that He makes an eternal covenant of grace with us and adopts us as His children and heirs. Therefore, He promises to provide us with everything good and protect us from all evil or turn it to our profit.

When we are baptized into the name of the Son, God the Son seals to us that He washes us in His blood from all our sins. Christ unites us to Himself, so that we share in His death and resurrection. Through this union with Christ, we are freed from our sins and accounted righteous before God.

When we are baptized into the name of the Holy Spirit, God the Holy Spirit assures us by this holy sacrament that He will make His home within us and will sanctify us as members of Christ. He will impart to us what we have in Christ, namely, the washing away of our sins and the daily renewing of our lives. As a result of His work within us, we shall finally be presented without the stain of sin among the assembly of the elect in life eternal.

Afterwards the minister prays Martin Luther’s “Great Flood Prayer” (Sindtflutgebet), adopted in almost every Reformed baptismal liturgy:

Almighty, eternal God, long ago You severely punished an unbelieving and unrepentant world in holy judgment by sending a flood. But in Your great mercy, You saved and protected believing Noah and his family. You also drowned the obstinate Pharaoh and his whole army in the Red Sea, and You brought Your people Israel through the sea on dry ground. In these acts, You revealed the meaning of baptism and the mercies of Your covenant in saving Your people, who of themselves deserved Your condemnation.

We therefore pray that in Your infinite mercy, You will graciously look upon this, Your child, and bring him/her into union with Your Son, Jesus Christ, through Your Holy Spirit. May he/she be buried with Christ into death and be raised with Him to walk in newness of life. We pray that he/she may follow Christ day by day, may joyfully bear his/her cross, and may cling to Him in true faith, firm hope, and ardent love.

Comfort him/her in Your grace, so that, when he/she leaves this life and its constant struggle against the power of sin, he/she may appear before the judgment seat of Christ, Your Son, without fear. We ask this in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, who, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, the one and only God, lives and reigns forever. Amen.[8]

More important than the liturgy, the Confession itself can’t be read to say baptism is a mere dedication. Article 33 confesses the truth of the sacraments in general. They “seal unto us [God’s] promises” and are “pledges of the good will and grace of God towards us.” Moreover, they “nourish and strengthen our faith.” They’re joined to preaching the gospel, “the better to present to our senses, both that which he signifies to us by his Word, and that which he works inwardly in our hearts.” Their goal is “assuring and confirming in us the salvation which he imparts to us.” Furthermore, through the sacraments “God worketh in us by the power of the Holy Ghost.” This is why we confess they “are not in vain or insignificant, so as to deceive us. For Jesus Christ is the true object presented by them, without whom they would be of no moment.”[9]

Article 34 on baptism proper speaks of the sacrament of baptism because it’s God’s work. Reformed Churches don’t view it merely as an ordinance or dedication. By baptism “we are received into the Church of God, and separated from all other people and strange religions.” It’s also “a testimony unto us that he will forever be our gracious God and Father.” Baptism is the sign “that as water washeth away the filth of the body…so doth the blood of Christ, by the power of the Holy Ghost, internally sprinkle the soul, cleanse it from its sins, and regenerate us from children of wrath unto children of God.”[10]

While the minister administers “that which is visible…our Lord giveth that which is signified by the Sacrament…the gifts and invisible grace; washing, cleansing, and purging our souls of all filth and unrighteousness; renewing our hearts and filling them with all comfort; giving unto us a true assurance of his fatherly goodness; putting on us the new man, and putting off the old man with all his deeds.” Because baptism is more than a dedication, it doesn’t “only avail us at the time when the water is poured upon us and received by us, but also through the whole course of our life.”[11]

In addition, the order in which an article falls in the Confession doesn’t determine meaning. An example is the doctrine of election. The Belgic places it (art. 16) after creation and providence, man’s creation and fall, and original sin (arts. 12–15).[12] The point of the Confession’s placement isn’t that election was somehow contingent upon or occurred temporally after the Fall. Instead, de Brès and the Reformed churches expressed election to make a pedagogical point.[13] Muller demonstrates that election was placed all throughout the loci of Reformed theologies for various reasons. Even Karl Barth recognized this in Church Dogmatics. Muller says writers such as Calvin, Musculus, Hyperius and Beza never intended to impute meaning to predestination based on its placement. This was simply a “way of teaching” (docendi via).[14]

An Implicit “Calvin v. the Calvinists” Argument

My second critique of the article under review is that it seems to have an undertone of the disreputed and so-called “Calvin versus the Calvinists” thesis. This thesis was exemplified in R. T. Kendall’s, Calvin and English Calvinism to 1649 (1980). Kendall argued that Calvin’s doctrine of election came in the context of Christ and salvation. Then later his successor Theodore Beza abstracted it under the doctrine of God. His thesis pits Calvin versus Beza;”warm, biblical theology versus cold, scholastic theology.[15]

Rev. Boonzaaijer “seems” to assume this paradigm. First, on the doctrine of election in the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession he says: “Both seem to be a prescient warning against the efforts of the Synod of Dordt…which did articulate clearly a teaching on predestination to death as well as to life” (59). He pits the sixteenth century Confession with the seventeenth century Canons. This overlooks the fact that the Belgic does express a doctrine of “double predestination,” too. Arminius perceived this and article 16 became the root of the controversy in the Netherlands. The Confession doesn’t express a “strong” version of double predestination, but it does confess a “softer” view:

We believe that all the posterity of Adam, being thus fallen into perdition and ruin by the sin of our first parents, God then did manifest himself such as he is; that is to say, merciful and just: merciful, since he delivers and preserves from this perdition all whom he, in his eternal and unchangeable council, of mere goodness hath elected in Christ Jesus our Lord, without any respect to their works: just, in leaving others in the fall and perdition wherein they have involved themselves.[16]

This “soft” view of the Belgic is also that of the Canons of Dort:

According to which decree he graciously softens the hearts of the elect, however obstinate, and inclines them to believe; while he leaves the non-elect in his just judgment to their own wickedness and obduracy. And herein is especially displayed the profound, the merciful, and at the same time the righteous discrimination between men, equally involved in ruin; or that decree of election and reprobation, revealed in the Word of God, which, though men of perverse, impure, and unstable minds wrest it to their own destruction, yet to holy and pious souls affords unspeakable consolation (1.6).[17]

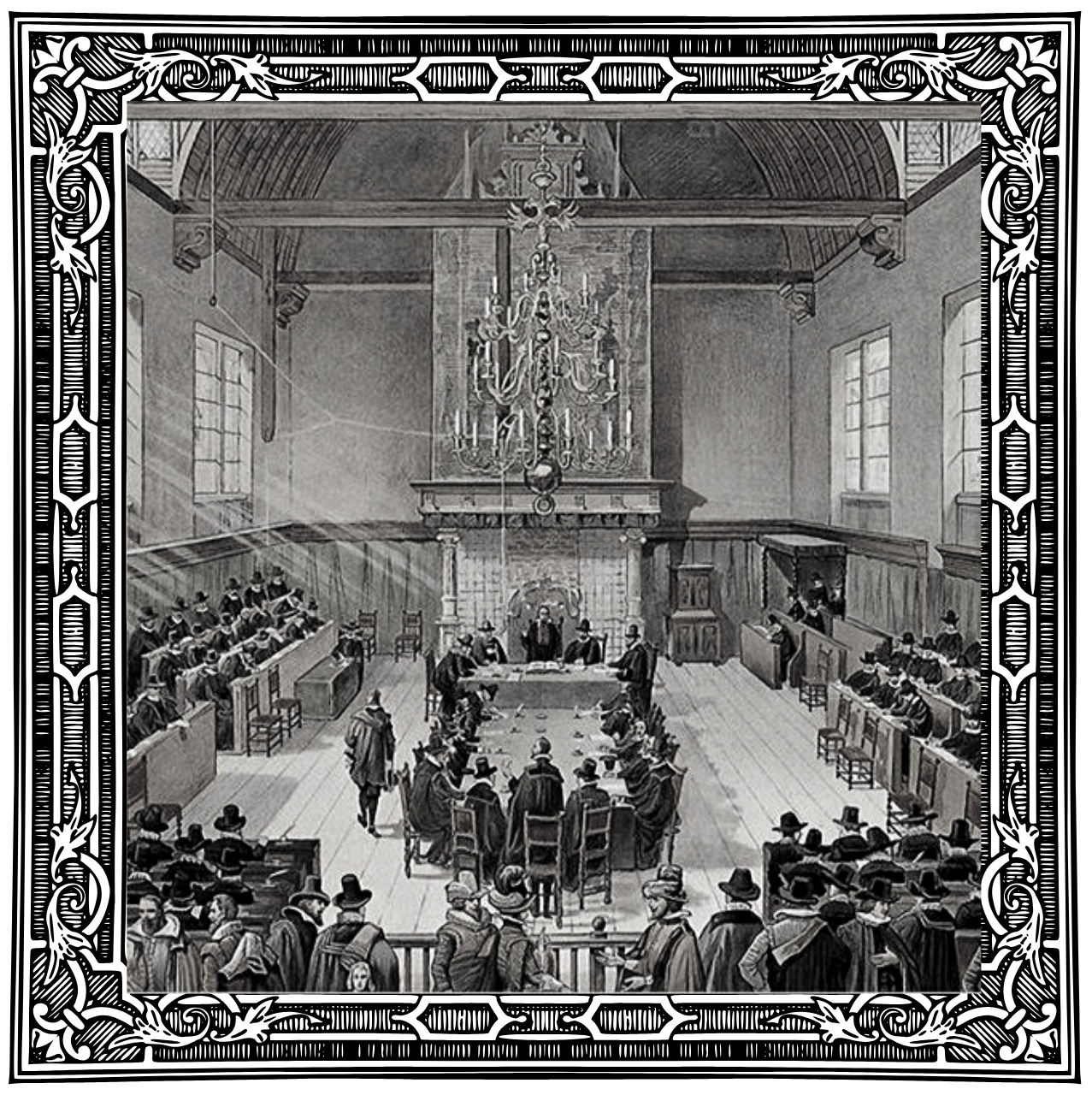

Let me also gently remind my Anglican brothers that the Synod of Dort was no “Dutch thing,” that is, merely a Reformed robber Synod in the small corner of The Netherlands. It was, and remains, the only truly ecumenical Reformed Synod with delegates from all corners of the Reformed world at the time. Delegates came from Germany (Bremen, Emden, Hesse, Nassau-Wetteravia, the Palatinate) and Switzerland (Basel, Berne, Geneva, Schaffhausen, Zurich). The delegates from France and Brandenburg were unable to attend due to religious pressure.

The Synod also included King James’ delegation from Great Britain. In fact, they were seated in the preferential place next to the officers of Synod, separated from everyone else. At the bottom of each head of doctrine the names of the delegates who signed them as their common faith included. We read the names of those Ex Magna Britannia: Bishop George Carleton, John Davenant, Thomas Goad, Joseph Hall, Samuel Ward, and Walter Balcanqual. They viewed the churches of the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession as one. Joseph Hall, in fact, preached on Romans 9 at the opening of the Synod:

. . . adhere to the belief which hath hitherto been received, and to the confession which you hold in common with the other churches. Which if you do, O happy Holland! O immaculate spouse of Christ! O most flourishing republic! Then at length this Church, which has been tossed about on the waves of jarring opinions, will sail into harbour, and will in safety smile at and despise the storms which are stirred up by the evil one . . . We are brethren, let us also be colleagues. What have we to do with the disgraceful titles of Remonstrants, Contra-Remonstrants, Calvinists, or Arminians? We are Christians, let us also be like-minded. We are one body, let us also be of one spirit. By that awful name of Almighty God, by the affectionate and gentle bosom of our common mother, by our own souls; and by the most holy bowels of our Saviour Jesus Christ, seek peace, brethren.[18]

The second reason why Rev. Boonzaaijer “seems” to assume the Calvin v. Calvinists thesis is that he make a claim about the seventeenth century that’s not the case: “Since Dordt, making Predestination the operative paradigm resulted in the formalization of an unwittingly cruel torture of souls, willing to leave the faith simply for the relief of being sure of God’s attitude” (59). Muller has handily dealt with the faulty foundation of the thesis that predestination post-Dort became the “central dogma”:

The attempt to describe Protestant scholasticism as the systematic development of central dogmas or controlling principles—predestination in the case of the Reformed, justification in the case of the Lutherans—was, at best, a theological reinterpretation of the Protestant scholastic systems based on the efforts of constructive theologians of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to rebuilt theological system in the wake of the Kantian critique of rational metaphysics . . . At worst, the central dogma theories are an abuse of history that cannot stand in the light of a careful reading of the sources.[19]

Moreover, Muller says the Reformed orthodox never thought the doctrine of predestination was an organizing principle of theology (locus de theologia), foundation of theology (principium theologiae), or even fundamental article of faith (articulus fundamentalis). Like Augustine and Aquinas, the Reformed considered predestination a sub-category of the doctrine of God, not the controlling doctrine of their theology.[20] This is expressed in the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession.

Polemics of Innovation

My final critique is in the title of Rev. Boonzaaijer’s article: “Continuity vs. Innovation.” This is more a polemical claim of modern Anglicanism than historical. Cranmer certainly didn’t make this claim against the Reformed on the Continent. He welcomed them to set up “Stranger’s Churches,” in fact. Rev. Boonzaaijer says,

. . . the 39 Articles can very well afford to speak as an established historic, orthodox and apostolic Church, for that is central to her understanding of her identity. The Continental reformers had such convictions, and quote the Fathers often, but only through a doctrinal and biblical connection through a long leap of a millennium and a half (59).

He speaks of the Continental churches as “a new movement.” In opposition, the English church is “the ancient and original, one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church reformed” (57). He calls the Belgic Confession a “defensive response of a new entity” (59) and “a separatist confession” (61). Then he says, “The Continental reformers were very aware of having initiated a new movement. While they quote the Fathers and invoke the Creeds to maintain unity, of necessity they had to be more defensive” (60).

Again, Rev. Boonzaaijer is more polemical than historical. One of the great questions the Reformation inevitably led to was whether or not the Protestant churches were churches.[21] Underlying all the issues between Rome and the Reformation on church authority and man’s salvation was this: whether Protestants were catholic or schismatic. What the Belgic Confession says about the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church was an ecclesiastical summary. Calvin, Peter Martyr Vermigli, and John Jewel all would’ve agreed that the Reformation continued the true catholic Church.[22]

This theme of the catholicity of the Reformed churches was common in the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession. Another example is the first Reformed confession in Hungary. It’s title is Confessio Catholica. We see it also in the words of John Knox who, like de Brès, was in Geneva with Calvin. In the Scotch Confession of Faith he wrote,

As we beleve in ane God, Father, Sonne, and haly Ghaist; sa do we maist constantly beleeve, that from the beginning there hes bene, and now is, and to the end of the warld sall be, ane Kirk, that is to say, ane company and multitude of men chosen of God . . . quhilk Kirk is catholike, that is, universal, because it conteinis the Elect of all ages, of all realmes, nations, and tongues, be they of the Jewes, or be they of the Gentiles, quha have communion and societie with God the Father, and with his Son Christ Jesus, throw the sanctificatioun of his haly Spirit (article 16).[23]

The purpose of such statements was to counter the Roman Catholic apologists’ argument that because Protestants had only recently formed, they couldn’t be true churches. The Reformers pointed to the chronological and geographical meanings of catholic as counter-argument. The church began before Rome came to be “mother” of the Western church. The implication was clear: the Reformers had left the Roman Catholic Church in order to reunite themselves with the true, catholic church. Rome left the true church.[24] Vermigli said the Reformers divorced Rome because of her adultery, causing the mother to become stepmother![25]

The Belgic confesses the church in its essence (art. 27) and its necessary communion (art. 28). Then it answers “which church must I be a member of?” (art. 29) There were Orthodox churches in Russian and Greek-speaking lands. “Utraquist” churches followed Jan Hus (from sub utraque specie, partaking of communion in both bread and wine. They led to the Bohemian Brethren (Unitas Fratrum) in the Czech-speaking lands of Bohemia. The Belgic churches left the Western Roman. There were also many “evangelical” churches—Lutheran and Reformed. In contrast to them all were various kinds of Anabaptists.[26]

Martin Luther was one of the first Reformers to speak of the external signs that identify the Christian church. In On the Councils and the Church (1539) he said:

Well then, the Children’s Creed teaches us (as was said) that a Christian holy people is to be and to remain on earth until the end of the world . . . But how will or how can a poor confused person tell where such Christian holy people are to be found in this world?[27]

He went on to give seven “signs” whereby one could know Christians had gathered. The signs were Word, baptism, Lord’s Supper, keys of the kingdom, calling of ministers, prayer and praise, and the life of the cross.[28] Two years later, he wrote Against Hanswurst: there have always been two churches—the true and false. Because of this, discernment in finding the church is necessary.[29] When Luther and the Reformers, the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession spoke of two churches and the outward marks, they were following Augustine. In The City of God, Augustine traced the two lines of Seth and Cain throughout Scripture. This demonstrated there have always been communities of the true people of God against the world.[30]

When King Edward VI died the Roman Queen Mary reigned. Those in the “Strangers” churches fled back to the Continent. Among them was Guido de Brès. He left London for Lille, close to his hometown of Mons. There persecution was a daily reality. His ministerial predecessor, Pierre Brully, had been burned at the stake. Such persecution forced de Brès to work secretly as a traveling preacher from 1552–56. He also wrote his first book, The Staff of the Christian Faith (Le baston de la foy Chrestienne). It was a basic textbook of theological commonplaces with sentences from Scripture and the church fathers. Its purpose was to show that the Roman Catholic Church was not the ancient church; rather the Reformed were.

Knowing and considering the war and combat that we daily suffer to maintain and keep the true and pure Christian doctrine of the ancient and true Church of God, against a sort and heap of glorious deceivers, which hide and boast themselves with false ensigns, of the name and title of the ancient Church, and of the ancient Doctors Let us rejoice in this, that we hold the true ancient doctrine of the Prophets, Apostles and Doctors of the Church.”[31]

Conclusion

In conclusion, Rev. Boonzaaijer’s article enables appreciation for each other’s confessional traditions. Both Anglican and Dutch are part of the Reformed family. The 39 Articles and Belgic Confession are Reformed Catholic confessions. Despite some serious critiques on methodological and historical-theological grounds, his article resurrects a godly attitude. Across geographic, linguistic, and confessional lines, our forefathers heard, read, marked, learned, and inwardly digested one another’s confessions as brothers with an international Reformed movement. Those of the 39 Articles and Belgic Confession, today, need to recapture this brotherhood.

[1] This article first appeared in The North American Anglican 2 (Spring 2009): 157–165. It’s a review article of John P. Boonzaaijer, “Restoration vs. Innovation: Comparing the Thirty-Nine Articles and the Belgic Confession.” The North American Anglican 1 (Winter 2008): 56–63. My text includes Page references to Boonzaaijer’s article.

[2] See Calvin’s letters to the English Church in Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters, ed. Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet, 7 vols. (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1983). See to Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset (5:182–98, 257–61, 315–17), to Edward VI (5:299–304, 354–55, 393–94), and to Archbishop Cranmer (5:345–48, 356–58, 398–99).

[3] Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation, Written During the Reigns of King Henry VIII., King Edward VI., and Queen Mary: Chiefly from the Achives of Zurich, trans. and ed., Hastings Robinson, The Parker Society, v. 37–38 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846-47), 24–25. Compare Calvin’s letter to Cranmer, Selected Works, 5:345–48.

[4] For a more comprehensive study of the background of the Belgic Confession, see Nicolaas H. Gootjes, The Belgic Confession: Its History and Sources, Texts & Studies in Reformation & Post-Reformation Thought, gen. ed. Richard A. Muller (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007), 13–58, and, Daniel R. Hyde, With Heart and Mouth: An Exposition of the Belgic Confession (Grandville: Reformed Fellowship, 2008), 7–24.

[5] Rev. Boonzaaijer notes that the Belgic Confession is “strongly influenced by Calvin – particularly his Institutes of the Christian Religion” (56). For scholarship on the historical antecedents to the Confession and its influences, see Gootjes, The Belgic Confession, 59–91; S. A. Strauss, “John Calvin and the Belgic Confession.” In die Skriflig 27:4 (1993): 501–17.

[6] See Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th Centuries in English Translation: Volume I, 1523–1552, ed. James T. Dennison, Jr. (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2008). Fo the Second Helvetic, see Volume II, 1552–1566 (2010).

[7] “Dedicatory Epistle to Philip II,” trans. Alastair Duke in Hyde, With Heart and Mouth, 502.

[8] See also Calvin, Institutes, 4.15.9; cf. 4.15.11.

[9] Schaff, Creeds, 3:424.

[10] Boonzaaijer, in speaking of the issue of the effectiveness of baptism, says, “Regeneration, however, is not mentioned.” Boonzaaijer, “Restoration vs. Innovation,” 61. We may disagree on baptismal regeneration, but the Belgic does speak of “regeneration”: et nous regenerant d’enfans d’ire en enfans de Dieu (French); nosque ex filiis irae in filios Dei regenerans (Latin). De Nederlandse belijdenisgeschriften, ed. J.N. Bakhuizen van den Brink (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Ton Bolland, 1976), 132–33.

[11] Schaff, Creeds, 426–28.

[12] What follows is an expansion of Hyde, With Heart and Mouth, 212.

[13] Richard A. Muller, “The Placement of Predestination in Reformed Theology: Issue or Non-Issue?” Calvin Theological Journal 40:2 (November 2005): 209.

[14] Muller, “The Placement of Predestination,” 194–204. The phrase docendi via comes from Hyperius’ Methodus theologiae, sive praecipuorum Christianae religionis locorum communium, libri tres (Basle, 1567), 182.

[15] For advocates of the Calvin versus the Calvinists school, see James B. Torrance, “The Concept of Federal Theology,” in Calvinus Sacrae Scripturae Professor, ed. William H. Neuser (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994); Torrance, “Covenant or Contract,” Scottish Journal of Theology 23/1 (February 1970); Basil Hall, “Calvin Against the Calvinists,” in G. E. Duffield, ed., John Calvin. Courtenay Studies in Reformation Theology (Appleford: Sutton Gourtenay Press, 1966); B. A. Armstrong, Calvinism and the Amyraut Heresy: Protestant Scholasticism and Humanism in Seventeenth-Century France (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969); Peter Toon, Puritans and Calvinism (Swengel: Reiner Publications, 1973); and the aforementioned, R. T. Kendall, Calvin and English Calvinism to 1649 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979). In response, see especially Richard Muller’s four-volume work, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics: The Rise and Development of Reformed Orthodoxy, ca. 1520 to ca. 1725 (2nd edition; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003).

[16] Schaff, Creeds, 3:401.

[17] Schaff, Creeds, 3:582.

[18] Cited in The British Delegation and the Synod of Dort (1618-1619), ed., Anthony Milton, Church of England Record Society 13 (Woodbridge : Boydell Press, 2005), 132. See also Mark Shand, “The English Delegation to the Synod of Dordt.” Brittish Reformed Journal 28 (Oct.–Dec. 1999). This article is also online: http://www.britishreformedfellowship.org.uk/articles/BRJ28/M.%20SHND%20ENGL%20DORDT.pdf

[19] Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, 1.125–26.

[20] Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, 1.126–29

[21] What follows is adapted from Hyde, With Heart and Mouth. 363–401.

[22] Calvin says this in his “Prefatory Letter” to Francis I in his Institutes. See also Vermigli’s “Schism and the True Church: Whether Evangelicals Are Schismatics for Having Separated from the Papists,” in Early Writings: Creed, Scripture, Church, trans. Mariano Di Gangi and Joseph C. McLelland, ed. Joseph C. McLelland (The Peter Martyr Library: Volume One; Kirksville, Missouri: Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers, Inc., 1994); John Jewel wrote “An Apology for the Church of England,” in The Works of John Jewel, ed. for Parker Society by John Ayre, 4 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1845–1850).

[23] Schaff, Creeds, 3:458.

[24] Vermigli, “Schism and the True Church,” 219.

[25] Vermigli, “Schism and the True Church,” 218, 221.

[26] On the fracturing of the western church before and during the Reformation, see Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books 2003), 3–52.

[27] Martin Luther, “On the Councils and the Church,” in Martin Luther’s Basic Theological Writings, ed. Timothy F. Lull (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, 1989), 545.

[28] Luther, “On the Councils and the Church,” 545–63.

[29] Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966), 41:181–219.

[30] The City of God, Books 15–18.

[31] The Staff of the Christian Faith, trans. John Brooke (London: John Daye, 1577), Preface.