I assume you are a skeptic of whether Jesus Christ was and is even real. I want to respond to your objections with the case for the cross. Perhaps you’re a seeker of truth with doubts and questions. I want to lead you closer to the truth. You may even be a genuine Christian yet struggling to believe in the “foolishness of the cross” (1 Cor. 1). If so, I pray my presentation reassures you of the truth and significance of Jesus’ cross and even enables you to present him to others.

We read in John’s Gospel, “There they crucified him” (John 19:18a). “There”—on a hill called “Golgatha” (v. 17) outside the gates of Jerusalem (Heb. 13:12) from noon until three in the afternoon (Matt. 27:45, 46). “They”—the Roman soldiers under authority of Pontius Pilate, the fifth prefect (governor) of the Roman province of Judaea from 26–36 AD; during the reign of Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (16 November 42 BC–16 March 37 AD); and at the instigation of the Jewish religious leaders under the high priestly ministry of Caiaphas, who was appointed high priest in 18 AD by the prefect who preceded Pilate, Valerius Gratus, and served until 36 AD. “Crucified”—the heinous method of torture and death used in ancient civilizations such as the Persians and Carthaginians, but was perfected by the Romans. “Him”—Jesus, who was born in Bethlehem, was raised in Nazareth, and lived in Judaea during the early first century. But did all of this really happen? If so, what does it all mean? What is the case for the cross?

The Historical Evidence

I’ll skip over the historical reliability of the Gospel narratives as this has been ably defended recently. Instead, I’ll present the historical evidence for Jesus’ existence and his crucifixion.

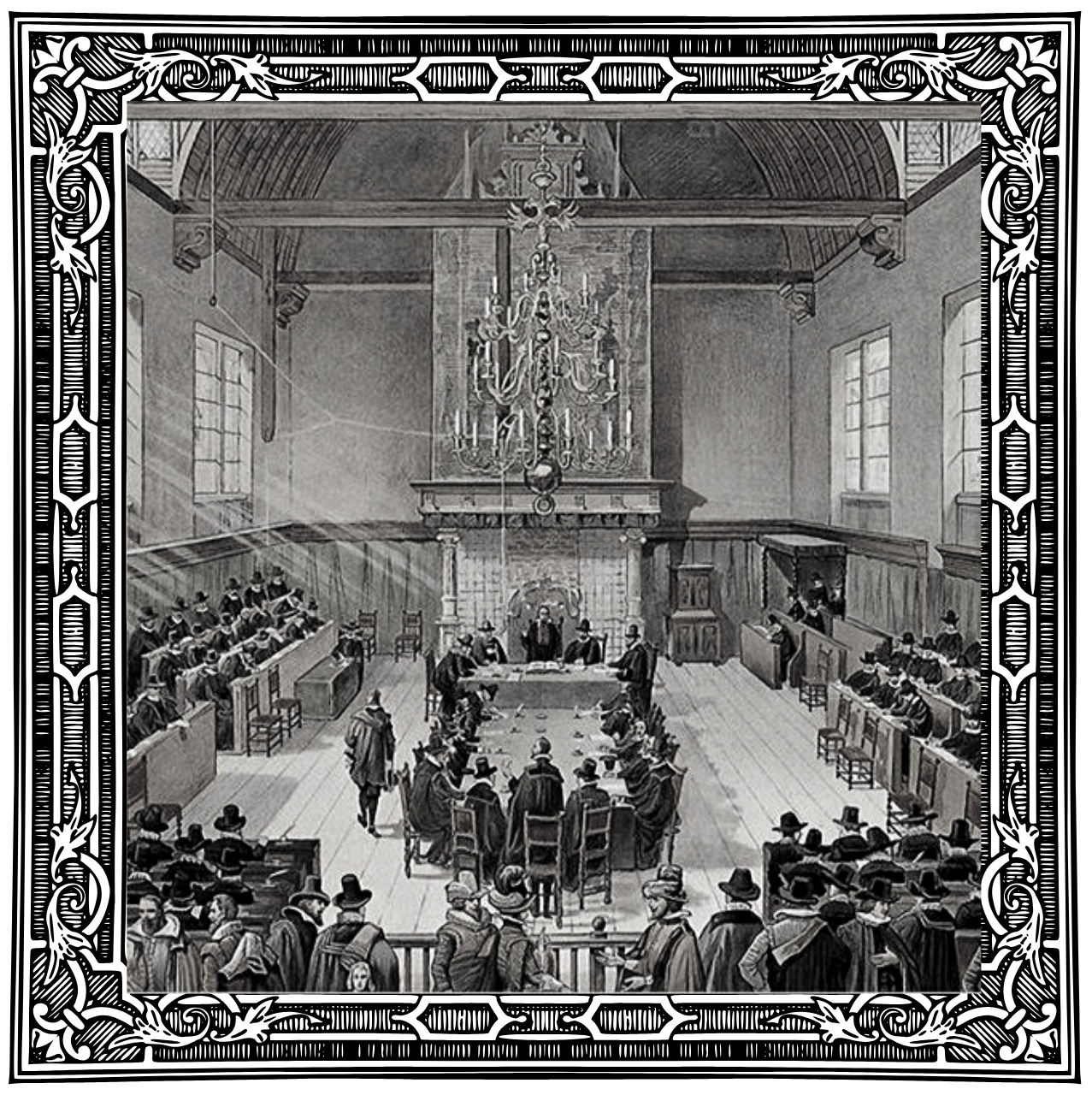

The Jewish Testimony

In their ancient writings, the Jewish rabbis don’t deny that Jesus either lived or was crucified. In fact, they positively stated that he was crucified. The Talmud—the authoritative tradition of sayings and teachings from the ancient rabbis—says, “On the eve of Passover they hung Jeshu the Nazarine…for sorcery…and enticing Israel.”[1] In early debates between Christians and Jews such as between Justin Martyr (100–165AD) and Trypho the Jew around 150AD, Trypho never denies the existence of Jesus.

What we take away from these sources is that the argument was not about whether Jesus existed or was crucified, but over the significance of his existence and crucifixion in light of the Old Testament.

The Roman Historians’ Testimony

In the ancient Roman writings that speak of Jesus we also never read them denying the existence or crucifixion of Jesus. For example, writing around 93–94AD, the Jewish historian for the Roman Empire Josephus (37–100AD), wrote in his Antiquities of the Jews:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day (18.3.3).

The Roman Empire’s greatest historian was Tacitus (56–120AD). In 116AD he wrote his monumental Annals. In a passage on the great fire of Rome in 64AD and Caesar Nero’s reaction to it he wrote: “Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus” (15.44). What we learn from the ancient Romans is that they spoke of Jesus and assumed he was just as historical as their greatest men such as Julius Caesar.

The Philosophers’ Testimony

Like the above, the philosophers never denied Jesus’ existence or crucifixion. Concerning Jesus’ crucifixion, the Stoic philosopher Mara bar Serapion wrote a letter from prison to his son sometime after 73AD, saying,

What advantage did the Athenians gain from putting Socrates to death? Famine and plague came upon them as a judgment for their crime. What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand. What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise King? It was just after that their kingdom was abolished. God justly avenged these three wise men: the Athenians died of hunger; the Samians were overwhelmed by the sea; the Jews, ruined and driven from their land, live in complete dispersion. But Socrates did not die for good; he lived on in the teaching of Plato. Pythagoras did not die for good; he lived on in the statue of Hera. Nor did the wise King die for good; he lived on in the teaching he had given.[2]

Another ancient philosopher and writer, Lucian of Samosota (125–180), was positively anti-Christian; yet, in a tribute to a Cynic philosopher in The Passing of Peregrinus, he not only derided Christians, but he said why: they worshipped “the man who was crucified in Palestine” (§11). He went on to describe Christianity as “denying the Greek gods and […] worshipping that crucified sophist himself” (§13).

“There they crucified him” (John 19:18a). Did this really happen? According to Jewish rabbis, Roman historians, and non-Christian philosophers, the resounding answer is yes! I haven’t even presented to you the fact of the reliability of the New Testament manuscripts! There are more than one thousand times more manuscript data for the New Testament than for the average ancient Greco-Roman author. Further, the extant manuscripts of these authors is no earlier than five hundred years after the time they wrote. For the New Testament, they are mere decades after. For example, the earliest manuscript of Tacitus is from the ninth century AD; yet we take what he wrote as factual and historical. Guess how many manuscripts of his we have? Three. We have five thousand seven hundred Greek New Testament manuscripts, ten thousand Latin manuscripts, and over one million known references to the New Testament in the ancient church fathers. One recent writer asks why the Gospels present the account of Jesus’ death with so many precise details of priests, governors, and emperors and then answers like this:

Because this death and resurrection are not the transposition into mythical form of an eternal cycle. Because the history of Jesus has no resemblance to the innumerable myths of gods who died and came to life again each year. Because this is a true story, and because Jesus was a real man and not the product of pious imagination. The Christian faith is no more attached to a myth than it is to a particular philosophy or symbol. It is attached to a man, a historical person who lived his human life here, on our earth.[3]

The Spiritual Significance

I say all this not to give you a bare history lesson. Just because someone really lived and died in the first century doesn’t automatically grant significance. What we are talking about, though, is serious because the historical Jesus claimed to be God in human flesh; he claimed to be the fulfillment of ancient Jewish prophecy; he claimed to be the only way to have reconciliation with a God you have offended. The case for the cross has spiritual significance.

The significance is that what happened to him was in fulfillment of ancient prophecies about him. The prophecy of Isaiah was given some seven hundred years before Jesus lived. What we read in Isaiah 52:13–53:12 describes Jesus’ life as the Gospels would go on to record. The prophet described his beating and flogging: “his appearance was so marred, beyond human semblance, and his form beyond that of the children of mankind…he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him” (52:14; 53:2). The prophet described Judas’ betraying him, his own countrymen delivering him, and his closest friends denying him: “He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief;and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not” (53:3). The prophet described the Roman method of execution: “But he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed” (53:5). The prophet described his trial before Pilate and his silence as he prepared to die: “He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he opened not his mouth” (53:7). The prophet described his being taken down from the cross and buried by Joseph of Arimathea: “And they made his grave with the wicked and with a rich man in his death, although he had done no violence, and there was no deceit in his mouth” (53:9).

Why did Isaiah prophesy the death of the Lord’s Servant, which in New Testament terms is Jesus’ death on the cross? Jesus was crucified unjustly. Even Pilate said, “I find no guilt in him” (John 18:38; 19:4). But his death was not just an injustice that we need to rise up and protest. His punishment goes to the deeper issue that it was not for his sins, but for the sins of others—ours. Over and over again we read in Isaiah that his death was on behalf of others:

Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows. (53:4)

But he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed. (53:5)

…and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all. (53:6)

…who considered that he was cut off out of the land of the living, stricken for the transgression of my people?(53:8)

… by his knowledge shall the righteous one, my servant, make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities. (53:11)

…he poured out his soul to death and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and makes intercession for the transgressors. (53:12)

So what’s the meaning of this “offering of the body of” the historical “Jesus Christ once for all” on the cross? (Heb. 10:10) He died to satisfy God’s own justice towards us sinners, of which there was “a reminder of sins every year” in the sacrifices of the Old Testament (Heb. 10:3). He died to pour out grace upon us sinners: “where there is forgiveness of these, there is no longer any offering for sin” (Heb. 10:18).

You see, the God whom the historical Jesus testified was real cannot just decide on a whim that some sins are forgivable and others aren’t; that would be unjust and God is perfectly just. Since sin is violating God’s just laws, every sin—however small—must be punished perfectly. But if God justly punished every sin as sin deserves, then where would grace be since he is also perfectly love? This dilemma of justice and love is where God shows his wisdom. In his wisdom God sent his eternal Son, whom we know as Jesus. He is divine but also became a real human being. As such he really lived and died on the cross both to take God’s justice due to us upon himself and to pour out God’s amazing grace to skeptics, seekers, and strugglers who simply put trust in him.

This is why the case for the cross of Jesus is so significant. Give yourself to him and he’ll take away your sins that separate you from God and you’ll experience acceptance with God.

[1] See David Instone-Brewer, “Jesus of Nazareth’s Trial in the Uncensored Talmud.” Tyndale Bulletin 62.2 (November 2011): 269–294.

[2] Cited in F. F. Bruce, Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament (1974; repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 31.

[3] Stages of Experience: The Year in the Church, trans. J. E. Anderson (Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1965), 31.